In an otherwise desolate land, with neighboring locations so harsh as to be named El Malpaís (The Bad Place), El Morro is a stunning oasis. The pool of water at the foot of this massive rock formation has sustained travelers for thousands of years. Indeed, evidence of these passers-by remain in petroglyphs and carvings that are preserved on the rock face. Native Americans, Spanish conquistadores, and American settlers have all passed by El Morro and left their mark.

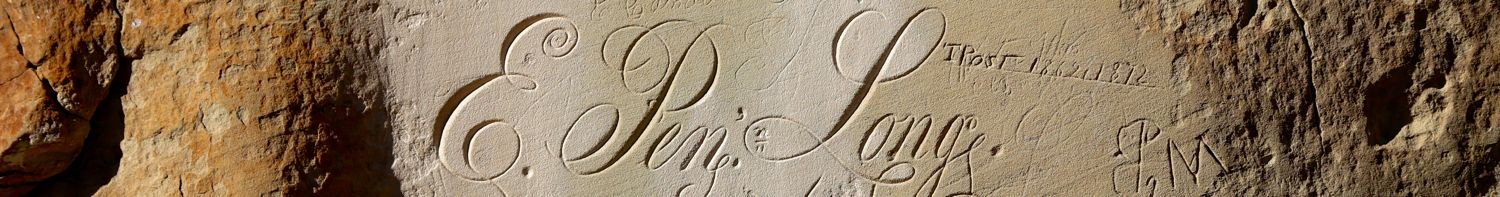

This sandstone promontory has gone by many names. To the Zuni Indians, it was “A’ts’ina”—translated as Place of writings on the rock. Spanish explorers and settlers called it El Morro— meaning “The Headland.” To the Anglo-American travelers, it was Inscription Rock.

Petroglyphs by Ancestral Puebloan, centuries before Europeans came to this land, document mountain goats, paw prints, and other symbols. Not only did native peoples stop by El Morro for water, but evidence of cliff dwellings on the top of the stone outcropping remain as evidence of communities that lived for decades in this area. Zuni indians mainly settled around the Little Colorado River drainage and traded with the Pueblo and other Southwest cultures. Atsinna Ruins, the largest of two ruined pueblos atop El Morro, housed up to 1500 people who lived in this 875 room pueblo around 1275 to 1350 AD. The people collected rainwater in reservoirs and farmed corn on the plains. To the Zuni people, El Morro remains a sacred space.

The Atsinna Ruins were already abandoned by the time Spanish explorers and Mexican settlers traveled through. Spanish conquistadores came to the southwest in search of the mythic golden city of Cibola. Francisco Vasquez de Coronado lead an expedition in 1540. Yet, unlike the immense wealth seized from the Aztec or Inca, Coronado was disappointed by the relatively simple agricultural lives of the Zuni and other Pueblo communities. Instead, this region became a missionary outpost for New Spain. Men such as Fray Augustin Rodriguez, a Fransiscan friar, stayed in the area to convert the local tribes. In 1598, Don Juan de Onate lead a group to settle New Mexico. His inscription on El Morro on April 16, 1605 is the first known European inscription. Despite such efforts by the Spanish (and, later, Mexicans) El Morro remained on the frontier’s fringe. While markings indicate many travelers that passed by El Morro, it was in an area that was constantly in contention between the local tribes and the Spanish or Mexicans.

After the Mexican-American War (1846-48), New Mexico became part of the United States of America and expeditions through the new territory began at once. In September 1849, Lt. James H. Simpson and artist Richard Kern took two days to document carvings from El Morro. These are the first recordings we have of the carvings. Settlers on their way to California often took a route by El Morro, and many left signatures and dates. Yet, with the introduction of the railway—a route that passed twenty-five miles north of El Morro—the iconic outcropping was no longer a major thoroughfare.

Over the centuries, El Morro has collected over 2,000 unique markings from petroglyphs, signatures, messages, to dates. The historic significance of these markings were recognized on December 8, 1906 when El Morro was declared a National Monument. From that point further marking of the stone was prohibited by the federal government. While some still try to add their own mark, at this point it is considered graffiti and the park does its best to preserve the historic markings.

Yet, this was not the end of all carvings on El Morro. The cliffs bear the more modern marks of the Civil Works Administration (CWA). In 1933, a CWA crew came to El Morro to create the Headland Trail, which visitors even today follow to view the thousands of carvings, ancient pueblo ruins, and magnificent views. The three mile loop trail is the best way to see El Morro and still benefits from stairs carved by the depression era crew almost a century ago.