With over 100 cattle brands decorating the entrance, there is little question that the Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum is a monument to the Texas cowboys and settlers that first developed northern Texas. Located in Canyon, just south of Amarillo, on the West Texas A&M University campus, the museum is Texas’ largest history museum and a well curated survey of the region’s past. That means a 12,500 square-foot maze of archeology, paleontology, ranching, hunting, and native people’s culture displays.

History of the Museum

The timing of the Panhandle–Plains Historical Museum could not have come at a more opportune time. When it opened in 1932, Texas was a state in transition. The Texas oil boom—which has been gaining momentum through the ’20s—was converting a rural state into an industrialized powerhouse. By the end of WWII, Texas would boast the highest concentration of refineries and petrochemical plants in the world.* Yet, in the mean time, scholars from the local West Texas State Normal College were working to preserve the history of their region. In 1921, the Panhandle-Plains Historical Society was first organized these teachers and students around the rich living history of Canyon, Texas. Even with the onset of the Great Depression, the society began a capitol campaign in 1929. With funds raised from community members, the society began construction of the elegant Southwestern Art Deco structure that now houses the Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum in 1932 and opened to the public in 1933.

History of Texas Settlement

The land that became the modern day Texas panhandle was originally the hunting land of Paleo-Indians who roamed the plains following fair weather and game. By the time Spanish adventurers came to the land, they found ancestors of the Apaches living nomadically on the buffalo. Even into the mid 1800s, the Plains Indians of this region remained relatively untroubled by European-American settlers. Yet, with the conclusion of the Civil War, European-Americans began challenging the tribes hunting privileges despite earlier treaties. Commercial desire for Buffalo hides spurred conflict that overpowered the local tribes and wiped out regional bison herds. The now empty land was open to new breeds of herds.

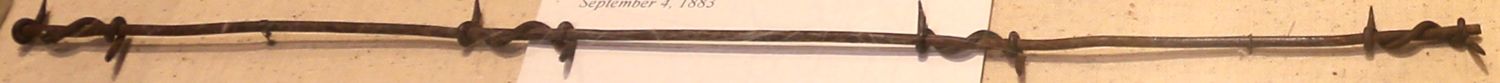

The expansive plains of the Texas Panhandle made for an excellent place to graze livestock. Early sheepherding quickly gave way to cow herding with the arrival of new settlers such as Charles Goodnight—who brought his cattle to graze in Palo Duro canyon in 1876. Yet, the Texas Panhandle and plains was not the easiest land to settle. Any land with surface water was quickly claimed leaving wide swaths of land where the only water to be found was in underground aquifers. Yet, with the high profit margins of cattle farming, corporations were infusing money into the ranching industry of Texas. These groups funded a more advanced infrastructure of wells and barbed wire fences. Ranchers also found a way to use one of the panhandle’s ample resources to access the more rare water: wind. Windmills powered pumps to bring water to the surface at rates that could even sustain herds of livestock.

Ranching was a cornerstone of the Panhandle economy for decades until dry-land farming and new irrigation techniques opened the Texas plains to farming at the turn of the century. By 1917, wheat and cotton joined beef as the Panhandle’s leading commercial products. Still, today, the Panhandle is a major processor of beef, and even the museum eloquently displays the transition from the early cowboys to modern ranching.

Visiting the Museum

Some of the most noticeable pieces in Pioneer Hall—the entry to the Panhandle–Plains Historical Museum—are artistically rendered saddles and murals of cowboys herding cattle. Yet the museum curators do not make the mistake of oversimplifying the roles of cowboys. Along with the classic garb of the cowboys are extensive collections of barbed wire and brands.

The basement level features a life-sized pioneer town complete with land office, jail, hotel, saloon, and original cabins which have been relocated to this underground site. The land office includes sample maps of land plots as might have been perused by settlers looking for their own slice of opportunity. While the hotel structure may have quite a few comforts, cabins in the back demonstrated the rougher reality that many new families faced when settling the region.

Even the seemingly unrelated paleontological wing of the museum includes an awesome display on the evolution of the North American Bison. As amazingly large as they may have seemed to early Europeans who came across these animals for the first time, the ancestors dwarf the modern bison. Truly a fascinating study.

An upstairs wing features one of the finest art collections in the Southwest. After perusing artifacts from the museum’s other wings, visitors can enjoy artistic interpretations of early native people, settlers, and cowboys.

Overall, any history buff should be more than satisfied with the broad spectrum of subjects covered by the museum. It is little wonder that 70,000 visitors come to the museum each year.

* Centered around Houston, TX.